Δ3 - Trash Gourmand

"It is always pleasant to see a young man fighting his way upward."

The other day my mom joyfully unearthed an ancient wrong I'd committed as a child, as is her right. She said, "Your aunt opened a can of Campbell's soup, and you ate it up like you'd never eaten in your life. I was in the kitchen every night cooking fresh chicken breast, fresh vegetables, and you would just sit there chewing it over and over, gna gna gna for hours. What you wanted was fish sticks, dumped straight out the freezer into some oil." Mom, I understand it must have been frustrating that your child preferred trash. I'm so sorry to tell you that I'm still that child, and the dumpster is still where I belong.

Today I've come to tell you about an obsession that found me this summer. In short, I was compelled to read a whole lot of garbage. These stories that consumed my summer are the barest, blandest, most basic of power fantasies; comparing them to frozen fish sticks would actually conceal the extent to which they barely function as stories. You might notice the passive tense in the previous sentences and think, "hey, aren't you avoiding responsibility for how you spent your summer?" That's right, because I didn't choose this! It was pure chance that tossed me into this particular pile of trash, and I never chose to be the kind of person that would stay there.

Now, when discussing trash stories, we won't get anywhere by asking "Is it good?" or even "Is it enjoyable?" That's not to say these stories (or beats, scenes, arcs within them) can't be good, fun, or even genuinely moving. They absolutely can be those things, but even when they are, those qualities aren't what brought the readers to the table. The right question is something more like "does it do the thing?" where "the thing" is compulsion. When you put down the book/comic/show, does it reach into your brain and command you to pick it up again? Do you need to read the next chapter, even when you think the chapters you just read were dumb as hell?

And, if you're me, the other 'right question' is this: after you've fought your way free of the compulsion, when you're walking among normal people on the street hoping they can't smell the garbage on you, do you look back on the story fondly? After everything, do you keep the first book on your shelf? Even if the series wasted your time, abandoned its premises, swerved into bizarre proto-fascism, mistreated and misused its characters, or fell short of its potential … do you keep the first volume on the shelf? Do you look at the generic cartoon characters on the cover and think "ah, it's these idiots. I love them." I think we're fooling ourselves if we act like we can only like things when they're good, and I'd certainly be a fool if I tried to talk about these power fantasy stories without admitting that I love them, both despite their shortcomings and because those shortcomings give them a particular quality (a flavor, maybe) that you can't find anywhere else.

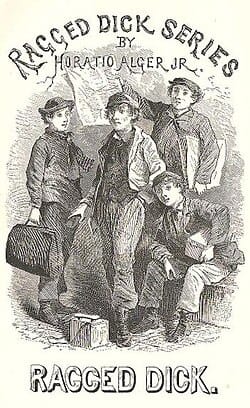

Pictures of the idiots I love. Yes, the visuals are too busy. No, I can't explain why the 5-year-old on the first volume's cover is wearing a miniskirt.

For my two readers

Hell Mode: The Hardcore Gamer Dominates in Another World with Garbage Balancing is an isekai light novel, manga, and (soon) anime that started life on the Japanese web novel platform Shōsetsuka ni Narō in November 2019. Right. So if I have two readers, one of you just nodded curtly, and the other is whispering something like "what the hell are you talking about?" For the sake of Reader 2, I'm going to take a moment to define some of those terms. Reader 1, please feel free to skip to the next section.

Web novels are the single best modern storytelling method longform stories that are published online, chapter by chapter. Unlike most classic (pre-digital) serial fiction,[1] which submitted to the editorial oversight of traditional magazines and newspapers, today's web novels are most often managed entirely by independent authors. Some authors host their stories on their own websites;[2] others choose to use an existing communal self-publishing platform,[3] where thousands of authors compete for the attention of millions of readers.

Light novels are longform stories published serially in print, volume by volume. The format originated in Japan, probably in the '70s[4] when publishers began to repackage and republish clusters of chapters from stories serialized in monthly magazines like Comtiq or Dragon. Each volume will be about 200-300 pages. With their breezy language and their occasional manga-style illustrations, they essentially feel like anime in print.

"Isekai" is a Japanese word that translates to "another world." It is also an SFF[5] subgenre, in which a person (usually from human Earth) is transported into another world (most often a medieval fantasy world). Transport methods include:

- reincarnation after death by truck

- reincarnation after death by bookshelf

- reincarnation after death by poison

- being summoned by a sorcerer

- just kind of waking up one day as a character in a book/show/video game

- portals.

Often the new world will operate by video game logic, with monsters, magic, dungeons, and abilities measured by numerical attributes (which you can improve by leveling up). Even when it's not a video game, the main character is often positioned to exploit experience from their previous life: if it's not their gamer skills, it's their adult fighting skills, their understanding of post-industrial technology, their memories of the plot of the book they're in now, their ability to look past their new world's arbitrary social biases, or having an iPhone. The genre has dominated the anime industry for the past 10-15 years. Its ubiquity, along with the way how all the stories are the same, leads a lot of intelligent nerds in the US to see it as annoying corporate slop. And yes, it is annoying, but it's not corporate - it's way weirder than that.

Shōsetsuka ni Narō is a Japanese web novel platform. With something like a billion monthly visits, it sits comfortably within the top 50 most visited websites in Japan. The website incubated the isekai genre in the mid-to-late 2000s,[6] and lots of folks more knowledgeable than me consider Narō to be responsible for anime's isekai boom. The story goes like this: in 2016, anime adaptations for 2 Narō stories aired, and both were massive hits.[7] If you're any kind of industry decision-maker, what can you do but look back at the vast collection of stories where those 2 came from? They'd struck gold, in the sense that there was a whole lot more gold to mine. And so we'd go on to get adaptations for a whole lot of series I'll refrain from listing, but which Reader 1 would be well-familiar with.

I can't overstate how many of these there are. Even with all the words I spent overkilling those definitions, I've dramatically simplified what this niche is and collapsed the diversity in how its stories function. Reader 1, forgive me. For now, I'm going to use Hell Mode as a representative example to explain what this genre is doing, and to ritually free myself from having to think about it all the time.

The Anime Event Horizon

Our main character is named Yamada Kenichi (for all of 6 pages), and he is a kind of strange that readers are expected to recognize. He manages to hold down a full-time job, but his video games are all he really cares about. Unfortunately, games these days are all too casual and easy. Looking for a challenge, he finds a game that offers a "Hell Mode," in which he would level up at 1/10 the normal speed, but with no upper limit on how powerful his character can grow. Upon clicking "Yes," he is reborn as Allen, a serf boy in a bog-standard isekai fantasy-type world. On day 1, your boy is grinding. He leverages his impeccable gamer skills to decipher his new world's metaphysical video game rules, train his "summoner" powers, and keep up with his superpowered peers. We meet the enthusiastic pink-haired sword-fighting girl from down the road, the "potato-faced" village boy who is also there, and a procession of charming[8] creatures created by Allen's powers.

The fantasy grind is Allen's sole, obsessive focus, until the day his father barely survives a close encounter with a monster. This harrowing experience leads Allen to develop a second obsession: protecting everyone he cares about from, um, everything. His efforts to do so (including singlehandedly hunting monsters, for meat, at 6 years old) earn him the attention of his local baron, who hires Allen as a manservant in his manor. Here, Allen annihilates his barony's monster populations, becomes friends with the baron's wizard daughter, and learns the truth of this world: a war is on. The monstrous hordes of the Demon Lord Army (no, seriously, that's what it's called) are poised to kill everyone in the world, and all those with "talents" (read: anime superpowers) are expected to go hold the line. So, obviously, it's off to anime fighting school, and then off to fight demons in the country of elves, and then off to visit a spread of fantasy places. We gather a ballooning collection of side characters, the world expands and expands, everything makes less sense every volume, the author forgets to characterize or describe people, and the story grinds slowly toward its eventual heat death.

My summary skipped some critical plot points: e.g. how the anime fighting school reunites Allen with his childhood friends, how the Demon Lord makes all the world's monsters stronger than they should be (the titular "garbage balancing," as in balancing a game's difficulty), how the gods answer prayers like game developers responding to their player-base. It also skipped everything that happens after the first 2 volumes. I would have liked to achieve a fuller, richer view of this weird thing and its weird choices. Unfortunately, I'm not quite sure these kinds of stories will allow us to know them without falling all the way in.

Although most stories can't be fully understood without being read, it's usually possible for their readers to return with a field report about, like, what happens in the plot. But with a certain kind of very long SFF, the events of the story's more advanced entries just straight up won't make sense if you haven't been inducted into the story's logic by its beginning. It's like how you can only access algebra after you learn arithmetic. I can say "Allen needs to make a holy fish cry on him so that he can summon S-rank monsters" (and it's great fun to do so), but for you to understand why Allen needs to make a holy fish cry on him, I'd need to explain that the tears of holy beasts become magical gems, and how Allen has always needed to sacrifice magic stones to summon his monsters, and maybe how ... I'm sure you get it. I call this phenomenon the Anime Event Horizon: there exists a threshold beyond which no information can be communicated to an outside observer.[9]

From Volume 3 onward, we're well beyond the event horizon. Luckily, those volumes are also not very good. I want to understand why this stuff works, and since the first 2 volumes contain everything that works best about this story, a few handpicked passages from these early entries should be enough.

Five-year-old serf girl vs. Fully armored knight

One of the things that "power" refers to is the capacity to shape the terms that others live by. When we call ourselves "the little guys," perhaps it is because the logic of our world depends on the whims and machinations of beings operating at scales too large for us to see, as if we are ants navigating between slats of a picnic table. If that is true for us, it's an even more essential truth under feudalism.

So it comes to pass that an order of knights visits Allen's village to stage a duel against his friend Krena, the pink-haired sword-fighter pictured on the first volume's cover. Her opponent: the knights' vice-captain, in full armor. Their stage: the village square, with all the village's residents standing by to watch. They will fight with steel swords, sharpened for battle. Krena is five years old; the blade the knights give her is almost as big as she is. Her father, believing he is about to watch his daughter die, begs for mercy, but there is no mercy to be found.

Krena, though, has always wanted to be a knight, and does not seem to understand that she's in danger.

The pink-haired girl was the only person who was smiling at the moment. She stared at the very first real sword she had ever held with sparkling eyes.

(Hell Mode, Vol 1, pg. 83)

The duel begins, and for about a minute, Krena holds her own. Then her opponent kicks her in the stomach. He is a grown man wearing iron sabatons; she is a little girl wearing a homespun dress. Even by anime rules, the hit is devastating.

There was no rule that they could only use their swords. The perfectly timed attack sent the girl flying through the air and crashing against a building. She crumpled to the ground, her head bowed. The wall had been made of solid wood, and yet the force of the impact had still left very conspicuous cracks on its surface.

"KRENA!!!" Allen yelled. He and [her father] tried to dash forward to help, but the knights closest to them wrestled them to the ground.

It really was too much for her! She is still only Lvl. 1 while that knight must have way more skills and experience from years of service. There was no hope of winning from the very start. What should I do?!

"What is-?! Stay still, kid!"

"Let me go, you asshole!"

Unfortunately, the man holding Allen down was far stronger than he was. The boy strained to get up, but could not budge an inch.

(Hell Mode, Vol 1, pg. 85)

So our main character is body slammed by an enforcer of the land's laws, unable to save his only friend from being killed in a profoundly unfair fight for reasons no one has bothered to explain. This moment is essential grounding for all the story that will follow. Later, when Allen has accumulated his wealth and power, when he is hearing requests from lords and antagonizing monarchs, when he gathers a personal army and blows off the fantasy UN, when he engages in outrageous corruption that risks tearing the fabric of international law, the story will need you to remember this moment of absolute powerlessness. We all know, going in, that by the end of this story, Allen will be the one making the rules ("dominate" is right there in the title); for us to feel good about that, this story decides that he should first be a victim of someone else's rules.

But, of course, Krena's not done yet. This is an anime in print, and if I had to describe the appeal of battle anime in one sentence, I would say that sometimes the five-year old serf girl can cut a knight's sword in half. She pulls herself to her feet, and:

Krena suddenly shouted, "RAAHH!" That moment, the cracked wall behind her exploded into smithereens as an aura exploded from her body, enveloping her in a shimmering contour that looked like a heat haze.

Wait, what?!

In the same breath, Krena charged forward once again. She leaped high up into the air and rotated furiously to add centrifugal force to her swing before bringing her sword down. The powerful attack descended upon Leibrand's head like a flash of lightning.

"Ugh!"

The knight needed to use both hands to block the slash, but the shock of the impact still ran through his body. The attack was so powerful that his feet sank slightly into the hardened dirt ground of the square.

(Hell Mode, Vol 1, pg. 86)

As I said, she hits the knight's sword so hard that it breaks in half. At that point, the knights' captain ends the duel. Krena's been having the time of her life, but even though she's disappointed that she won't get to fight anymore, she manages to be a graceful winner.

"Whaaat?" Krena asked in an unsatisfied tone, as if she had not had enough. "No more?"

"That's right. The fight is over."

The girl's shoulders slumped a little, but then she picked herself back up. She trotted over to [the knight] and bobbed her head. "Thank you very much! You're very strong, old Mr. Knight!"

(Hell Mode, Vol 1, pg. 88)

There is a tension here, between three different kinds of power.

- The state's power to make and enforce laws: someone offscreen decided that these knights are permitted (or required) to strike down a little girl in the middle of her village. Despite her family's furious, desperate desire to protect her, they cannot resist - to resist would not only be illegitimate, but punishable, most likely by death.

- Anime superpowers! These enable Krena to fight a grown man and win. This sort of power allows the story to emphasize the will of individual people; it also allows us the satisfaction of seeing someone we like overcome odds that should, reasonably, kill them. You might also imagine what kinds of problems this world's rulers need to navigate, knowing that some of their subjects are individually strong enough to shrug off their laws.

- Force of personality. Just as Krena's irrepressible, bubbly enthusiasm about knights(!) and fighting(!) is endearing to me,[10] it is also a power that can move other characters in the scene. When these knights return to the story in Volume 2, they do so as allies. In this world, as in ours, it matters if people like you.

These three modes of power challenge each other, force responses from each other, and carry the characters (and the world) farther and farther from the beginning's status quo. That dance is one of the engines that drives these stories.

Carrying a monster carcass home

The story's early chapters also have a second engine: the swiftly widening mismatch between the main character's capabilities and what everyone else expects of him.

For most people in Hell Mode's world, growing stronger (or leveling up) requires a healthy amount of effort. For Allen, growing stronger requires 10 times that much effort. Even with that disadvantage, he's so committed to the grind that, by the time he turns 8, he is unreasonably, frighteningly powerful. He's also the only person in his life that knows how strong he is - like many isekai protagonists, he chooses to conceal what he can do.[10:1]

In his village, it's not too hard for Allen to get away with killing monsters or training his summoned creatures or whatever nonsense he gets up to. His parents know that he is unusually wise, and they trust him. Things get a lot harder for him in Volume 2, after he's hired as a manservant in the house of his feudal lord. Killing monsters is the only way to level up; unfortunately, there aren't many monster-hunting opportunities in the gardens or the dining room, and the work is too demanding for Allen to slip away. He gets two half-days off per week, but that's not enough time to make it out to the countryside, where all the monsters are. But he's good enough at his job to collect the goodwill required to negotiate. He asks his boss, the butler, for one full day off per week; now he can spend the entire day hunting. Success!

Until the day the butler pulls him aside to say, "Hey, Allen, we've noticed you go out all day, from before sunrise until after sunset; also, you're a child. I think I need to know where you go and what you do there." So Allen, reluctantly, explains:

"I've been hunting monsters," Allen replied truthfully.

"You've been hunting monsters?"

"Yes, sir. On my days off, from morning to night, I've been hunting monsters outside the city."

The butler's eyes widened in surprise. He felt as if he was looking at the very concept of absurdity given the form of an eight-year-old boy.

(Hell Mode, Volume 2, Chapter 2)

When Allen says that he's been hunting monsters, we know that he means saving adventurers from bands of goblins. But the butler, looking at a small child, assumes that the "monsters" in question are the harmless jackalopes ("horned rabbits") that hop around near the city gates.

Apparently [the butler] was under the misconception that Allen had been hunting horned rabbits close to the city walls. The thought that Allen was hunting goblins hours away had not even crossed his mind.

"There's no need to hide it. You've been selling them to a butcher's for some pocket money, yes?"

(Hell Mode, Volume 2, Chapter 2)

So we can immediately see three reasons that Allen's choice to hide his powers is helpful for the story.

- These social obstacles give him something to do besides kill monsters all day, and his efforts to kill monsters anyway create drama.

- The social obstacles also help clarify the story's stakes: we all know that Allen will succeed at killing the monsters, but will he manage to do so without his boss finding out?

- There's a potential energy that builds up between the reality of what he's doing and what other people believe, like charge gathering on a capacitor. They're all underestimating him! How satisfying will it be when everyone finds out what he's capable of?

In this case, the charge releases right before the midwinter festival. The baron is expected to throw a big feast, but he's broke. The baron's son, knowing that Allen likes to hunt, asks him to go get a white deer, a massive stag with horns wider than a man is tall. Allen agrees. The baron's son is joking; Allen is not.

It requires a bit of ingenuity (a deep hole, a provoking spell, and a climb up the monster's shaggy back to slit its throat), but Allen manages to kill a deer, drain its blood, and drag its body back toward the city. Because the deer is much bigger than him, the baron's guards cannot see him underneath its body.

The commotion grew larger and larger by the minute.

"A monster's gotten onto the premises!"

"Gentlemen-in-waiting, grab your weapons! Someone, call the knights!"

[...] [Allen] dropped the white deer in a fluster so that they could see his figure clearly.

Boooooom.

The monster was so heavy that the moment it hit the ground, a tremor rumbled through the ground and blew snow away. Both those looking on from the second floor and those who had exited the mansion froze with shock, with some even falling on their rear ends. Most of them had never seen a monster up close in their life, and now a huge, white beast had seemingly walked into the grounds. The next thing they knew, however, it had transformed into Allen's form. Their minds scrambled to comprehend what they were seeing.

Ugh, that was really heavy. I guess my level is still a bit too low to carry something like that by myself.

[The butler] pushed through the crowd to confirm the situation for himself. "I- Is that you, Allen?"

"Yes, sir, it's me. I've just returned. Young Master Thomas told me to hunt a white deer, so here it is." [...]

The butler started when he recalled the exchange at dinner several nights ago. No one present had taken the conversation seriously, himself included. However, it was true that Allen had firmly declared that he would indeed bring a white deer back.

At almost sixty years of age, very little surprised [the butler] anymore. However, ever since Allen came to the mansion, he felt as if the perception of normalcy that he had built up over his entire life was slowly but surely being eroded away. He struggled to remain upright despite feeling his common sense crumble internally.

(Hell Mode, Volume 2, Chapter 3)

As a reader, you've been in Allen's head for more than 50,000 words. For him, the most remarkable thing about killing this monster was its weight - it's not especially convenient to bring back. For everyone else, this monster is a major threat that can overwhelm a dozen adult men standing shoulder to shoulder. That a child could kill and carry a white deer is unthinkable for a normal person; for Allen, it's Tuesday. Two incompatible models of the world face each other; an arc of electricity leaps across the gap.

Your body, between teeth

Even in a world where killing monsters makes you stronger, most people aren't interested. The world may work by a video game's logic, but that doesn't change the human instinct to avoid dying. They see a monster and think, there's something that could kill me. That could be my blood around its mouth, and my body between its teeth. That's certainly how I would feel. Take the murdergalsh:

A huge figure over five meters tall towered a slight distance away. There was something in its hands; when Allen took a better look, he realized it was a horse that had already lost half of its body. The monster was in the middle of eating the rest of it, chewing loudly.

That's a murdergalsh?!

Allen had heard the murdergalsh described as a large wolf, but what he was seeing could hardly be called such. At the end of front legs that looked like human arms, it had large fingers that also looked especially humanlike. Worst of all, its face was a revolting cross between human and canine.

(Hell Mode, Volume 2, Chapter 6)

No! No thanks. I'm all good.

To be fair to Allen, our favorite freak, interacting with this particular horror doesn't seem fun to him either. Unfortunately, he is in a story, and we all know about Chekhov's murder-wolf: if it rips off your mantlepiece in Act 1, you'll have to stab it in the eye in Act 3.

It happens like this: Allen and Cecil (the baron's wizard daughter, pictured on the cover of Volume 2) are kidnapped for unremarkable political reasons. They manage to escape, but it's a long journey through monster-filled wilderness before they can reach home's safety. One of the monsters in the wilderness is the murdergalsh. It finds them. There's no one nearby who can help. Allen could probably run away, but then it would kill Cecil. So, it has to die.

The fight goes pretty well, until it doesn't. The murdergalsh, bloody and desperate, grabs Allen and starts to squeeze the life out of him.

Allen was supposed to have died a while ago being crushed in this way. Sure enough his bones shattered and he spat up blood, but he managed to hold on by using Leaves of Life liberally. Several minutes later, the murdergalsh suddenly loosened its grip, grabbed Allen by his head, then chomped on him with an affected air. Its fangs pierced his abdomen, sending blood exploding like a fountain. From her position in the distance, Cecil crumbled to her knees, mumbling Allen's name in a small voice filled with despair.

(Hell Mode, Volume 2, Chapter 13)

As situations go, this is as bad as it gets. But Allen is built different - where I or anyone else would be panicking, he stays remains remarkably methodical. He has healing powers, so he'll simply use them to offset the damage. He knows this monster likes to play with its food, so he'll let it bring him closer to its face. And then, as promised, he'll stab it in the eye.

Where everyone else in Hell Mode sees a life, Allen sees a game. That doesn't mean he treats the world lightly, but it does mean that he can exercise his "hardcore gamer" skills in mortal situations. If I was being eaten by the creature described on these pages, my thoughts would be a wordless scream communicating something like, "Oh no, I am being eaten by the most horrible thing I've ever seen. I am experiencing blind panic and I'm certainly going to die." When Allen is being eaten by a murdergalsh, he thinks "I'm taking damage. I should probably heal." His ability to look at the world sideways is the most interesting thing about his character, at the character level, the core promise of this story's premise.

Solemnly agreeing to do what you already wanted

When Allen returns Cecil to her father's house, the baron offers him anything he might desire as a reward. The story has been piling on clues that there's something big going on offscreen. Officially, the kingdom is at peace, but noble children, sent off to serve somewhere abroad, come back in body bags. Knights reference their time on the front lines. Mithril mines are operating at full speed, but the weapons and armor are nowhere to be found. Allen asks for an explanation about what the hell is going on. So we learn about the Demon Lord Army, the global alliance that holds it back, and the academies where children are trained to die in combat. We also learn that Cecil will certainly be sent to fight in that war, to follow her older brother into a family grave.

The baron cannot stand to lose another child. It must be hard for him to ask someone else's child for help, but he has seen this child perform miracles, and I'm not sure anyone could turn down a miraculous opportunity to protect their daughter.

"Please attend the Academy with Cecil and protect her on the battlefield."

[...]

Right now, before [Allen's] eyes, was a feudal lord in the throes of despair after having his father, brother, and recently, even his son killed by the army led by a Demon Lord. And his request was to protect his one and only daughter, preventing her from meeting the same fate.

There's no doubt; this is a quest. You can also say that the plot is finally moving. I see; in this world, it takes four years to trigger the kind of quest that you'd normally get the second day after arriving in town.

"My lord, I, Allen, shall protect Lady Cecil with my very life," Allen declared

(Hell Mode, Volume 2, Chapter 14)

Let's ignore, for a moment, how Allen transmutes another human being's desperation into the language of video games. Instead, we can understand this exchange as the story's first and most important answer to the powerlessness Allen felt during Krena's fight (I told you that the story would want you to remember it). A volume and a half ago, Allen was being wrestled to the ground by this lord's knights. Now the man is begging him to protect his daughter.

We don't need to be proud of all our fantasies. Reader, maybe you're a healthier person than I am, but I cannot deny that I've wasted hours of my life imagining how I would respond when those who've wronged me come to me for help. Will I scoff (a single expel of breath through my nose, not even a chuckle) and turn away? Or maybe I'll shrug and say, "you should have thought about that when you took my last slice of pizza out the fridge." No, no, no, I'll do what they're asking without mentioning their prior trespass, and they will know, finally, the depth of my goodness, and the vast distance between the places waiting for us in heaven.

This scene is carefully balanced so that Allen can fulfil multiple such fantasies at the same time. The powerful man (who wronged him once) is grovelling for his help. Because Allen chooses to do the "right" thing, the reader can bask in his magnanimity. And, critically, Allen is only agreeing to do what he wanted to do anyway! He wants to go to anime fighting school and fight against the demon army, because that's what he would do in a game.

Hell Mode may be a representative example of the genre, but it's not particularly good. Its limited quality makes it easier to decipher the workings of the story's inner mechanisms, especially compared to more competent stories that build better surfaces to hide their gears. Which is to say, Allen's thoughts (in italics above) say the quiet part out loud: none of these characters are people to him. They are quest-giving NPCs, useful party members, and resources to protect. Of course, the story doesn't consider them people either. The most important thing about (commercial, mainstream) video games is that they're fun to play. If the game is built on quests, then those quests must consist of fun things the player wants to do. That's fine in a video game, because the player and their main character are not the same person — I'm just having fun, but Link/Hornet/Geralt/Aloy/Ezio/Sora are working themselves into the ground, throwing themselves into danger, and experiencing the hardships that good dramatic storytelling is made of. It's only a problem if the main character is also the player, such that the quests are all things the character already wanted to do. In that case, the logic of the world has to contort itself to his whims. Other characters are only permitted to desire things that are aligned with what Allen wants: otherwise, they become villains, and the story decides that it's legitimate to crush them.

The story wants you to remember what it feels like to be powerless. Unfortunately, if you are to stay on the main character's side, it also needs you to forget.

Broken pieces of a national story

The slow movement toward power (and then toward greater power) is such an essential part of this genre that some people just refer to them as "power fantasies." This is usually meant as an insult, indicating that these stories have no depth or meaning beyond the base fantasies they satisfy for their reader. I prefer to read the term as a specifier: these are fantasy stories about power, in the same way portal fantasies are stories about portals. However, that reading still emphasizes the endpoint, when the centerpiece of these stories is actually the journey: from pawn to player, from zero to hero, and from rags to riches. The techniques with which isekai power fantasies articulate that journey resonate across languages, and not only for the readers that enjoy them. There is also resonance with at least one other English-language genre, which we might find stirring in its grave. Which one? I've already named it.

In United States history, there is a period between the late 1870s and the turn of the century that we call the "Gilded Age." The era earned that name because our robber barons and corrupt officials were so much richer than everyone else that their blatant displays of wealth served to conceal the poison at the heart of our society, like a layer of thin gold over seeping lead. When we learn about the Gilded Age in middle school, our textbooks will usually dedicate a couple paragraphs to the popularity of "Rags to Riches" stories, in which a lovable, industrious street urchin works his way to the top of society because in America, anyone can make it (wipes away a tear). These stories were an important part of our national story. I mean, they offered a fundamentally untrue model of the world, but they were an important part of the story anyway. It turns out that one of the ways to handle unrestrained wealth inequality is to just say, "no, actually it's really fair how the wealth is distributed. All you have to do is work." Or, to quote one of the stories directly:

"[...] A good many distinguished men have once been poor boys. There's hope for you, Dick, if you'll try. [...] If you'll try to be somebody, and grow up into a respectable member of society, you will. You may not become rich,—it isn't everybody that becomes rich, you know—but you can obtain a good position, and be respected."

(Ragged Dick, Or, Street Life in New York with the Boot-Blacks. Chapter VI)

What I've just quoted is the very best-selling of Horatio Alger's overwhelmingly successful books. In the US, we remember Alger as the author of rags to riches stories, not least in our middle school history textbooks. Notably, though, our textbooks often don't tell us his books' titles, probably because - well, just look at it. You can't say Ragged Dick to middle schoolers. You can barely get away with saying it to adults.[11]

Ragged Dick tells the inspiring story of a 12-year-old boy's rise to respectability and success in 1860s New York City. We first meet Dick as a boot-black, a shoeshine boy, making a hard living on the streets. He has no parents to speak of, and he can afford neither clothes nor rent. However, after encountering one (1) nice rich boy, Dick takes some goddamn responsibility for his life: he stops wasting all his money on plays and dice games, he opens a bank account, and he pools money with another boy for a room in a boarding house. The two boys save money for a private tutor so they can learn to be respectable, and, eventually, a ridiculous stroke of luck earns Dick a "place" (a job) in a store! Then it's on to ballroom dances with girls their age, lucky real-estate investments, and all the other markers of fame and fortune both.

These (Ragged Dick and its sequel, Fame and Fortune, or, The Progress of Richard Hunter) may be the worst books I've ever read. Their titles aged shockingly poorly, but the content aged even worse. In the 20th century, people in the US decided that, actually, children shouldn't need to work to have somewhere to live, food to eat, and teachers to learn from. Looking back, Alger's smug moralizing about these children's failures to responsibly manage their finances is ... upsetting. Horatio, they're 12: of course they'll spend their money at the theater. Even worse, he really did mean well. Alger instructed his publisher to send free copies of the books to any lodging house (homeless shelter) that asked for them, "In order to reach as large a number of these boys as possible". What an awful country we had.

Anyway, despite my reluctant love for Hell Mode and my proud hatred of Ragged Dick, the comparison between these stories is instructive. On one hand, their structures feel surprisingly similar:

- Number go up - I didn't mention this in my summary, but Hell Mode is always showing you statblocks for Allen and his teammates. These lists of numbers let the reader track how the characters grow stronger as they find innovative ways to kill monsters at snowballing scales. Ragged Dick treats the balance of Dick's bank account in the same way. We constantly check in with the number, and as it increases, it opens new possibilities and concerns for the story. Dick doesn't level up, but he might as well. And as one nice rich man says in the second book, "It is always pleasant to see a young man fighting his way upward."

- Compulsion - It's hard to describe this feeling if you haven't experienced it. Even though the book isn't good, and the events in it aren't interesting, there's something almost addictive about seeing those numbers rise. The question that brings you back to the page isn't "what will happen next?" It's more like "how will the characters turn this advantage into further advantage?" It's the growth drive incarnate - in Ragged Dick, we're literally watching someone accumulate capital.

- Never take an L - If that growth drive does drag you back to the page, the story won't reward you with any proper stakes. The main character is not permitted to lose anything irrecoverable. Alternatively, the story is not permitted to take anything the main character cares about without giving it back. There might be danger: Allen and his team fight a demon much stronger than them; Dick is framed for larceny. There might even be losses: one of Allen's friends dies in combat; Dick's pocketbook is stolen. But it's essential that everything turns out fine in the end - if possible, the hardship should be transmuted into a hidden opportunity, and things should turn out even better than they were before.

On the other hand, thematically, these stories really are quite different. One is presented as fantasy, and the other is meant to be instruction. Ragged Dick invented a version of the world where job opportunities for homeless children were fair. Where the rags to riches story insisted that its fantasy world was real, the isekai offers a literal separation: the main character travels from our world to one where they can succeed. Perhaps there's something to learn, here, about what this genre's choices capture, articulate, and/or conceal about political-economic conditions in Japan and Korea - I don't know enough to say, but things seem pretty tough for workers in both countries. It does seems notable, though, that the genre is increasingly popular among US audiences as our country descends into its second gilded age. This time, we can't bring ourselves to pretend that everyone (here in reality) will be okay.

Even in the other world, it's not fairness (or even equality of opportunity) that most isekai stories aspire to. Instead, the fantasy is that you can be transported to a place where the rules of engagement work in your favor. Where Ragged Dick is essentially a story about assimilation (to succeed, you must first learn how to save your money, how to buy a suit, how to talk proper, and how to behave in respectable society), Hell Mode imagines a world where your place in society depends on knowledge, skills, and behaviors that you, as a reader, are likely to already hold dear. You can win in life by being good at video games. And, critically, in this new gamer's world, you're the only person who has ever been a gamer. We're not describing a world where everyone can make it. It's a world where the power structures are still rigid, but you're the one on top.

Hands on a keyboard

When people start writing a story, they usually aren't thinking about the massive political currents their work might resonate with. I hope that no one will read the previous section as an attack on Hamuo, Hell Mode's author. It is noble to make trash, and I really enjoyed my time with the trash Hamuo made. Besides, I'm happy for him: he gets to live his dream! He's achieved a career as a writer, writing about the things he cares about most. They're gonna make an anime out of his story! And if we need to articulate what the story's core fantasy is, there's a much gentler reading available to us.

In my summary, I mentioned that Allen (at 6-years-old) develops an overwhelming motivation to protect his family. Let's take a look at that moment:

Back when he had been Kenichi, Allen had been playing games ever since he was seven or eight years old. Of the countless games that he had come across, not once had he chosen to pick it up or not based on who the protagonist's parents were. After all, it was just a piece of inconsequential lore that had no bearing on the enjoyment of the game itself.

But then he was born to Rodin and Theresia. Every day of his life in the world, he had watched the two of them living their lives to the fullest up close. Mash eventually came along. And now, there was a third baby in Theresia's belly.

The last traces of childishness seemed to seep out of Allen's face as a powerful sense of responsibility welled up from deep within him. He felt as though he had woken up in a way. Six years, and he was finally reincarnated in the fullest sense of the word. [...]

"I swear I will protect this family."

(Hell Mode, Vol 1, pg. 128-129)

Let's set aside the question of whether the story achieves the goals it establishes here. Hell Mode wants to be a story about a manchild realizing that there's more to life than video games. More specifically, it wants to be about that man's second chance to live his life right. If I have wasted hours fantasizing about being in a position to refuse my enemies help, I have wasted days fantasizing about what I could do if I could start my life over. It's not only compelling because of what I'd be able to achieve (although I really would kill it at university) — it's compelling because I understand, now, how precious the people that raised me were. In many cases, I only came to understand how much I owe them after it was too late to pay them back.

In Hell Mode's afterwords, Hamuo writes a bit about his personal life. In Volume 9, he describes his father's death. Sometimes, there is a live wire hidden somewhere deep in another person's writing. Reading it, the wire touches you, and suddenly the current that animates them is running through you too. Hamuo writes, "Unfortunately, I don't think I've been able to repay my gratitude to him. I can't call myself a devoted son."

It's impossible to read Allen's unwavering commitment to his family as anything but an expression of his author's feelings. Hamuo, you won't ever see this, but I'm sorry that you lost your dad, and I'm sorry that you feel like you disappointed him. I'm almost certain that he loved you plenty, but I think you already know that: it's right there in your book. But I do understand how you feel. I wish I could do better by my family too.

Oh, and Hamuo? Sorry, but I think 10 volumes of this story was enough for me. I wish you the best of luck with the rest of the series. But you know your boy will be dropping back in for the anime.

Also: Mo. I need a word with you. Listen, I appreciate what your efforts with the art in these books. I can tell you're doing your best. Let's just try to avoid drawing 5-year-olds in miniskirts from now on, okay?

Habari Gani?

- If you'd told high-school Me that one day I'd be living in Stockholm and writing 20 page essays for fun ... man. This one has been on my desk since late June. Originally, I wanted to cover much more of the genre's breadth. There's a whole lot of weird and interesting stuff to write about, but I think I'll leave all that for later, or for others.[12] If you want to write about any of those (or challenge what I've asserted here), please do!

- I've been thinking about what to do with this newsletter's "monthly" schedule. It was a lot of fun to spend a couple months chasing down this idea, and I want to leave myself the freedom to do that when I'm driven to. But I also want to practice by writing many things, and the "news" part of the newsletter doesn't work as well if I only send it once a quarter. I'm going to Dubai for the Futures Forum in a few weeks! It would be a shame if I have to wait until I finish composing a long yap about Monster of the Week (or whatever) before I tell you about it. So, here's what I'm going to do: shorter, less ambitious posts. I'll still try and keep the monthly schedule during periods when I'm working on bigger essays, but I will give myself permission to post fragments and musings and unrefined ideas. Get ready for some quantity.

- My friend Charlotte, her friend Andy, and I are putting together an interdisciplinary collaboration/residency/workshop in Scotland this February. It'll be in an old house out in the Dumfriesshire countryside, and we'll be working together to understand emergence by making something new together. Artists, scholars, and practitioners of any sort are welcome to apply. More info on Charlotte's very cool website.

- My family's efforts to sell prints of my dad's paintings continue. We've set up a second shop on Etsy. My mom and I will also be doing some analysis of the art - my dad was working through some pretty deep stuff, actually. We've been surprised by how much there is to say. You can sign up for updates from our business mailing list, and you can see all the art on our main store.

- The report from the African Futures workshop I helped facilitate back in March is out! I'm really proud of what we did, and I'm pretty proud of the report too. I think it works as a fairly approachable explanation of what I spend my days doing, and it did manage to capture the richness and magic of the futures the workshop generated.

- Autumn passes swiftly in Stockholm. The leaves start falling at the beginning of October, and by now they're mostly gone. My favorite part of the season is the fog: it rises at night (which comes earlier every day). It stretches sounds farther than they should go, and when you go out into the city's forests, the streetlights will cast the trees' shadows into midair. This is a good place, even when it rains for four days straight.

That's all for now. Thanks for reading, and I'll see you next month (aspirational).

- e.g. Charles Dickens, Alexandre Dumas, Horatio Alger, Hajime Kanzaka ↩︎

- British writer qntm hosts 4 novels and a whole lot of short fiction on his website. US author Andy Weir originally published The Martian on his blog (as well as classic internet short story "The Egg" - Andy Weir wrote "The Egg," in case you didn't know that). Canadian author Wildbow maintains a constellation of wordpress sites for his 7 novels. ↩︎

- Like Wattpad or RoyalRoad in English, Webnovel in Korean, Jinjiang Literature City in Chinese, or Shōsetsuka ni Narō in Japanese. ↩︎

- Although the term wouldn't show up until the '90s. I have no idea, man, this appears to be one of those categorical questions that greybeards burn through forum pages arguing over. ↩︎

- An umbrella term for Science Fiction and Fantasy. Also horror. Also alternate history. Also climate fiction, speculative memoir, and speculative epic. Basically a general term for any speculative fiction that's not too self-conscious to hang out with the "cool" kids ↩︎

- For more details on what "incubation" means in this sentence, and on how the genre reproduces the tone and logic of fanfiction, please check out Kim Morrissy's definitive account on AnimeNewsNetwork. ↩︎

- These were Konosuba: God's Blessing on this Beautiful World and Re:Zero: Starting Life in Another World ↩︎

- Listen, I won't try to argue that Allen's summons are well-characterized. However, it is just true that my desire to see what new summons he might unlock was the main force that pushed me through Volumes 6-10. Is that because I'm a weirdo? Maybe. munch munch munch ↩︎

- Because a black hole has no size, the radius of its event horizon is determined exclusively by its mass. Because wordcount is a pretty clear analogue to size for stories, wordcount will almost certainly affect the radius of the Anime Event Horizon (i.e. how early in the story you stop being able to explain it to someone outside). For now, let's say the radius is proportional to the amount of nonsense in the story, but inversely proportional to wordcount, such that the determining factor can be understood as density of nonsense, measured perhaps in nonsense per sentence or nonsense per page. More research is needed. (This is a joke for my physics homies, don't worry if you don't get it) ↩︎

- It was in this chapter that I realized Hell Mode had me. I'm a little embarrassed to admit how well Krena's characterization worked on me. I am not a complicated man, and I do not require depth in my enthusiastic sword girls. I want the girl to be strong, I want her to swing the sword, and I want her to be happy while she does it. ↩︎ ↩︎

- In 1868, "dick" probably hadn't yet acquired the meaning we most often use it for now. Keep that in mind when the narrator of this book informs you that the other boys call our main character "Ragged Dick," but his government name is Richard Hunter. From Alger's perspective, the way we read those names today would have been completely unforeseeable. That really shouldn't stop you from making fun of him, though. ↩︎

- Further research might include the following. • How more competent versions of the isekai power fantasy generate even stranger thematic problems, like the accidental(?) fascism that emerges in Solo Leveling and Shield Hero because the stories refuse to frame protagonists' straightforwardly evil actions as problematic. • How the the genre's treatment of power is different when the protagonists are female, both in battle-focused stories (e.g. Bofuri: I Don't Want to Get Hurt, so I'll Max Out My Defense) and in in the romance subgenre (e.g. My Life as the Villainess: All Routes Lead to Doom or Trapped in a Soap Opera). • What's going on with the ones where the main character replaces the villain in a story they're familiar with (e.g. The Extra's Academy Survival Guide, The Greatest Estate Developer, both of the romance stories I mentioned above) - they appear to believe some very strange things about redemption, love, and the villains' right to live. ↩︎